The COP 21 Final Draft of the Paris Agreement has been released (see here for the text). After months of preparations and weeks of negotiations, the text concludes the drafting phase of the agreement. It's been fun following the ups and downs of COP 21, and a special thanks goes out to the Centre International de Droit Comparé de l'Environnement and FIU's College of Law, Sea Level Rise Solutions Center, and Institute for Water and the Environment for inviting me to the conference and allowing me to participate. The process (and blogging!) isn't over, as countries now need to ratify the agreement through their own domestic political processes, and of course, the agreement needs to be, you know, implemented. But for the moment we can step back and take stock of what the Paris Agreement means for international climate action. 5 thoughts:

The mood in Paris is optimistic

It's been a while since an international climate conference concluded on good terms. The last major effort in Copenhagen was panned as a failure, breeding cynicism that a climate deal could ever be reached. While the Paris Agreement has its faults (see below), it at least succeeded in bringing countries together to get started (if belatedly) on this business of climate change mitigation. The conference birthed the "high-ambition coalition" which includes both poor and rich nations, and many of the world's biggest polluters were enthusiastic about ambitious mitigation targets:

One of the most unexpected developments in Paris is the biggest polluters coming around to the idea of setting an even more ambitious target of 1.5 degree. Canada, Australia, European countries, China, and the United States have all spoken in favor of recognizing the damage above 1.5 degrees.

The final text adopted the less ambitious goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees, but nonetheless, it's encouraging that on a philosophical level countries are realizing that climate change must be addressed. Now they can decide how.

5-Year Reviews are In

I wrote at the outset of the conference that there was some consensus forming around the idea that countries' emissions (and progress in meeting emissions reductions) would be reviewed every five years. That would allow the international community to monitor progress (and laggards) while providing a basis to adjust emissions reduction targets if climate science paints an increasingly bleak picture. 5-Year Reviews ended up being much more contentious than expected, as China pushed for more ambiguous reporting requirements. The United States pushed hard to keep the 5-Year Reviews in the agreement, and in the end they were successful. Based on its negotiating stance, the US should expect to lead the review effort, providing financial and technical assistance to developing countries to conduct the reviews. The Reviews will begin in 2019.

Decarbonisation is Out (more or less)

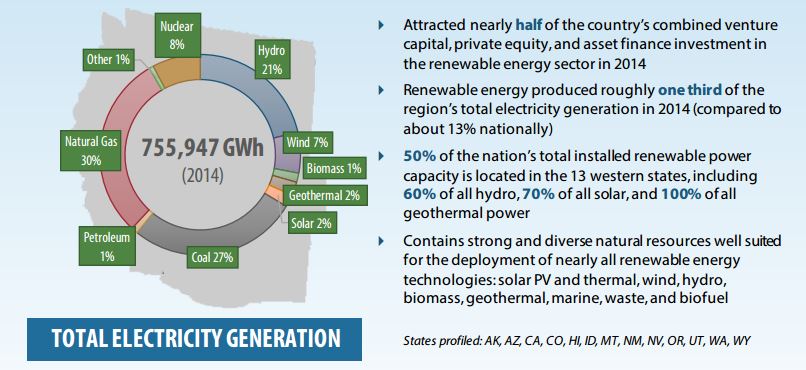

One of the more ambitious goals of previous drafts of the agreement was complete decarbonisation by 2050. In other words, to produce 100% of energy through renewable sources within 25 years. It was always a bit of a reach, but the fact that decarbonisation was a talking point and negotiating item at all was surprising to some. The final draft only calls for carbon neutrality (no net increase in carbon emissions) sometime in the second half of this century. A far cry from decarbonisation by 2050.

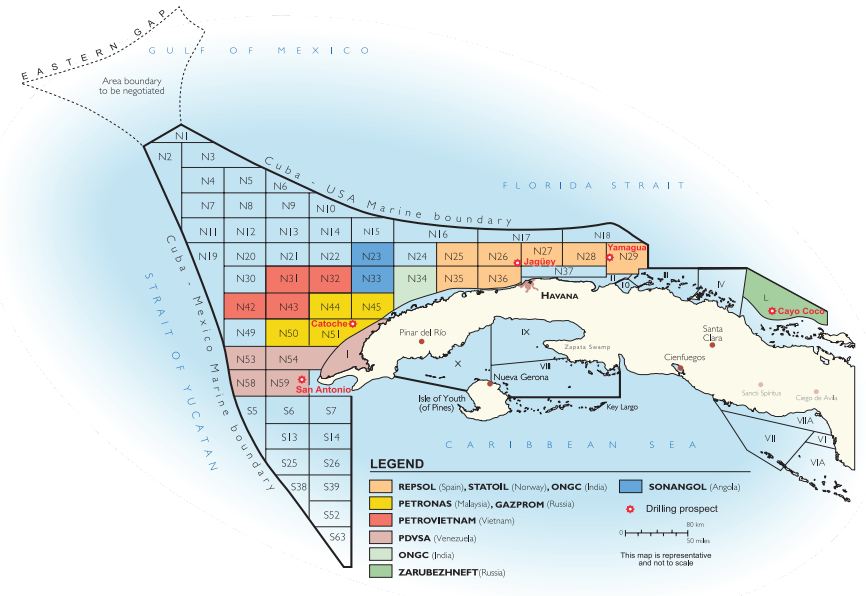

Climate Finance tabled for now

The most divisive issue at COP 21 may have been the differentiation in responsibilities between rich and poor countries. I wrote about this on Tuesday, particularly the "loss and damage" provisions that developing countries were desperate to include. "Loss and Damage" provisions are in the final draft, but lack any meaningful obligations. In fact, the preamble specifically interprets the loss and damage provisions of the text to not "provide a basis for any liability or compensation." In other good news for rich countries, the financial obligations can was kicked down the road. The previous commitment to provide 100 billion USD was maintained as a floor, while an increase in that amount was tabled until 2025. A short-term win for developed countries, but one that doesn't resolve the underlying tensions between rich and poor countries when it comes to climate change.

The scope of the Paris Agreement was appropriately narrow

Anytime an environmental issue makes it onto the international agenda in a high-profile way, there's a temptation to piggy-back by making the issue a proxy for every other environmental issue. Technically it's pretty easy to do, as environmental challenges are so intertwined that addressing one can be reasonably argued to be a prerequisite for addressing another. And so it was at COP 21, where many were campaigning hard for the climate agreement to meaningfully address the role of women, indigenous groups, management of the oceans, and a host of other climate-related problems. I spoke at an event on Thursday that was focused on human rights and climate change, and most of my co-panelists spoke with disappointment that the text was unlikely to address human rights. These focus issue groups will be disappointed that the final draft does little (if anything) to address their core concerns. Unfortunately, that probably wasn't realistic in the first place. It was hard enough for negotiators to agree to a text that was narrowly focused on carbon emissions. In fact, the conference went longer than expected in order to get it done. Climate change does implicate countless other environmental challenges, but to add them all to the agenda would have precluded agreement on a more focused topic. Many groups will be disappointed by the final draft, and they are right to continue pushing for progress, but at its core the Paris Agreement was about carbon emissions. That other related issues were dropped along the way shouldn't detract from the fact that for the first time the international community has a meaningful framework from which to continue addressing climate change.