Energy Firms Move Into Cuba

/Image: Jorge R. Pinon, 2012.

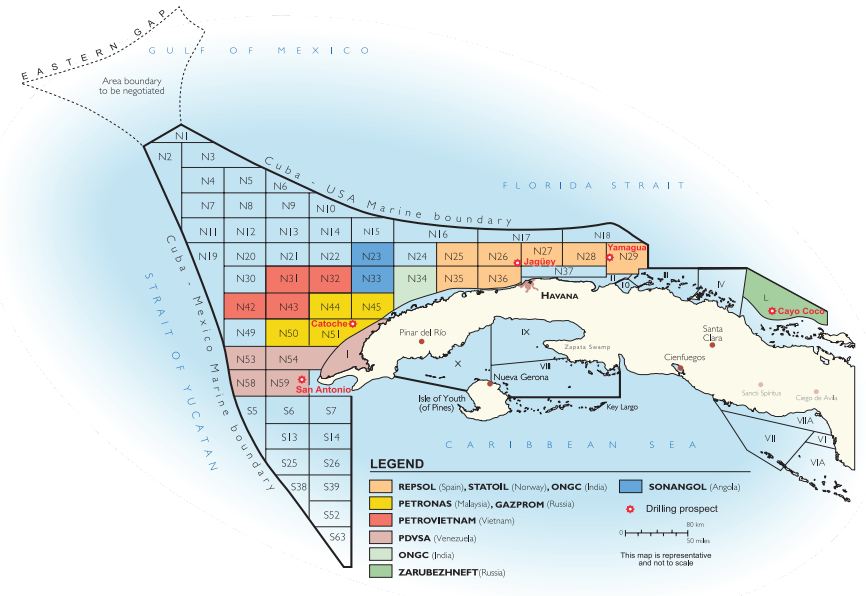

Back in May I predicted that, with the warming of US-Cuba relations, energy companies would start lining up for a chance to explore Cuba's potentially lucrative offshore oil and gas reserves. Firms have been showing interest, but perhaps not as enthusiastically as some (including myself) predicted. French energy giant Total allegedly struck a deal with the Cuban government, but later denied the claims. Since then energy firms from Angola and Australia have signed deals to explore and potentially exploit offshore oil reserves.

So far these oil and gas deals have been limited, in part because Cuba has retained certain nationalization requirements for foreign companies. It also appears that the absence of US energy firms, due to the ongoing embargo, removes some of the industry's biggest players from the market. The embargo's conditions also limit the extent to which foreign firms can use American equipment and technologies, and this might significantly increase the risk of environmental damage.

[Former EPA Administrator William Reilly] noted that Cuba's expertise lies with drilling in shallow waters. U.S. drilling equipment and technology is widely regarded as the best and safest in the world, he said, and American companies might highlight that expertise in a push for access to Cuba. “The companies could well make the case — and I would help them make the case — that it would advance the safety of Florida and the environment and the Gulf if American companies ...were doing the drilling in Cuba,” Reilly said. “There ought to be a blanket exemption for anything relating to spill control.”

The "blanket exemption" refers to the requirement that US companies obtain a special license from the federal government to conduct oil spill clean-up activities in Cuban waters. At present there are too few licenses to ensure that a spill would be effectively contained before hitting the coast of Florida. According to one estimate, less than 5 percent of the equipment, vessels, and services used to clean up the Deepwater Horizon spill would be legally available to respond in Cuban waters. Whether French, Angolan, or Australian energy firms are compliant with embargo terms or not, the US remains unprepared to unleash the full force of oil spill clean up capacities.

It is unclear when these companies will actually start extracting oil and gas. Cuba claims production could begin in 2016 with the lifting of the embargo. US energy heavyweights are taking notice, and some included Cuba in their lobbying disclosure statements:

Shell Oil Company, the U.S.-based subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell, reported spending almost $2.5 million from April through June lobbying the federal government on a laundry list of topics—including issues related to Cuba sanctions, disclosure reports show. Chevron U.S.A. Inc. reported shelling out almost $2.2 million to influence the federal government on issues including the “lifting of Cuba sanctions.” Meanwhile, Halliburton spent $100,000 plugging multiple matters, including “Cuba status,” the disclosures show.

In October a high-level meeting will take place in Havana in order to "work on establishing uniform environmental and safety policies for offshore drilling throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea." While safety and the environment will be on the agenda, industry reps will surely be keen to discuss the lifting of the embargo in order to facilitate the involvement of US firms. And while that may be a worthy topic, US representatives would do well to prioritize the easing of restrictions to licensing requirements that impede oil spill recovery efforts.