When Cuba and the United States announced in December 2014 a mutual desire to re-establish and improve diplomatic relations, it was clear the process wouldn't take place overnight. Members of Congress remain skeptical, while Cuba has a long ways to go to satisfy western standards for human rights and open governance. But the writing is on the wall, and governments and foreign investors are lining up for their chance to tap into the Caribbean's largest country (by population and land area) and its vast natural resources. Last week French President Francois Hollande became the first European leader to visit the island since 1986. He brought with him a contingent of French business executives, just as diplomats from Japan, the EU, and Russia brought their own private sector leaders in recent visits. French oil giant Total is now rumored to have struck a deal to explore off-shore oil reserves in Cuba's waters. More foreign investment agreements are sure to come this year.

Lifting the Cuban embargo is sure to transform Cuba's economy, and in many ways, the mere anticipation of it already has. But it will radically transform Cuba's environment as well. The sectors most likely to see dramatic change implicate environmental laws and regulation that were not designed to absorb rapid changes: transportation, agriculture, tourism, and oil and gas development. I will be following US-Cuba relations in the coming months with an eye toward what this all means for the environment. First up: regulation of off-shore oil and gas development.

It would be too simplistic to say that lifting the embargo would be good or bad for the Cuban environment, and that's true of the oil and gas sector in particular as well. On the one hand, economic isolation has likely depressed oil and gas exploration in Cuban waters, keeping sonar, construction, shipping, and drilling constructions out of marine ecosystems, while keeping fossil fuels in the ground. The lack of activity means the likelihood of a catastrophic oil spill reaching the shores of Cuba or Florida is low. On the other hand, a lack of diplomatic relations with Cuba means the US doesn't have a bilateral agreement in place to deal with an oil spill. The isolation also prevents collaborative research between US and Cuban researchers from looking at ways to improve natural resources management and disaster planning. Florida state law, for example, prohibits state university researchers from conducting research in Cuba or Cuban waters. Lifting the embargo may reverse both trends, increasing oil and gas development as well as contingency planning and research.

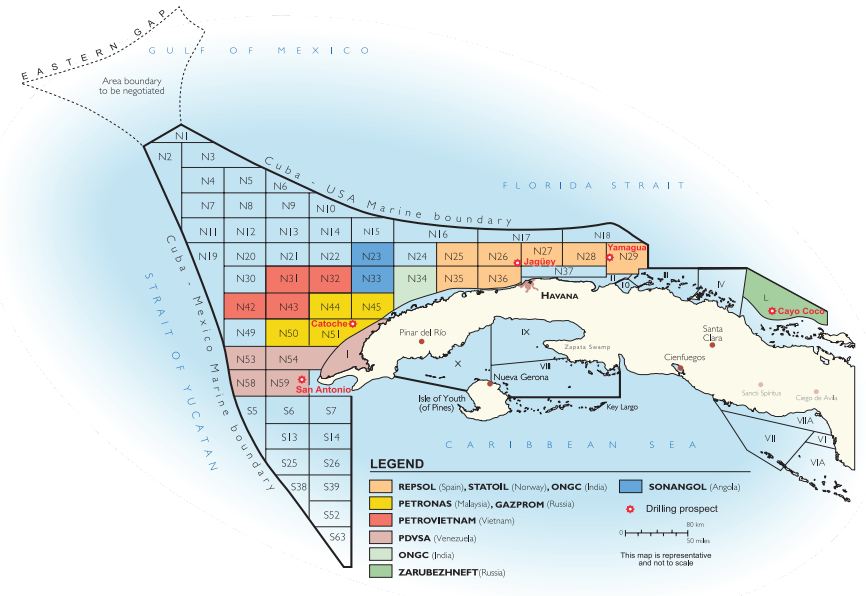

Cuba understands that its energy status quo is not ideal. It produces about half of its own oil, mainly for industrial use. The other half it receives from Venezuela in exchange for healthcare support. Relying on a single source for half of your energy needs is not ideal under normal circumstances, much less when that source is undergoing political turmoil, so Cuba has an interest in diversifying. It has plans to increase renewable energy production (98% of electricity comes from fossil fuels), but sees its offshore oil and gas reserves as the path toward energy independence. Cuba estimates that it's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ, waters over which it has oil and gas rights) contains around 20 billion barrels of undiscovered crude oil. The US Geological Survey has estimated Cuba's EEZ to contain around 5 to 7 billion. Either way, Cuba intends to find and develop its reserves, and has already partnered with China, Brazil, and Venezuela to develop critical infrastructure.

There are reasons to doubt an immediate expansion of oil and gas development in Cuba, including low oil prices and new opportunities in Mexico. But drilling is likely to occur sooner or later, and that's where US-Cuba agreements, regional disaster planning, and US laws are ill-prepared. An oil spill off the northwestern coast of Cuba would hit Florida within 6 to 8 days. And yet, Cuba and the United States don't have a bilateral agreement in place to deal with that scenario. The US and Mexico have a bilateral agreement that regulates oil and gas development in the Gulf of Mexico, establishing safety standards, emergency protocols, and inspection procedures. A similar agreement is needed to protect the Florida straits. Domestically, US law impedes oil spill response by limiting the number of licenses issued to companies that are pre-approved to provide oil spill services in Cuban waters. As mentioned above, it is difficult for researchers to study Cuba's coastal and marine environments without federally-approved licenses and visas. And if a spill originated in Cuba's EEZ, the Oil Spill Pollution Act wouldn't be able to extract compensation for damages. The Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund could provide relief, but it lacks meaningful and readily-accessible relief funds.

Sooner or later Cuba's off-shore oil and gas reserves will be exploited. Its reliance on Venezuela and a potential increase in demand from economic development and tourism will force it to uncover every rock. Cuba can help itself by diversifying into renewable energy, particularly as a source of foreign investment. Negotiations between the US and Cuba should prioritize cooperation over oil and gas development and emergency response, and come up with a treaty that enumerates safety standards, roles, and responsibilities. Domestically, the US should make it easier for US companies to participate in oil spill response efforts, and ease restrictions on researchers to simulate environmental impacts and collaborate with Cuban universities. The dominoes are starting to fall, and for the sake of the Caribbean environment and coastal communities in Cuba and Florida, international and domestic laws must be in place to minimize the damage.