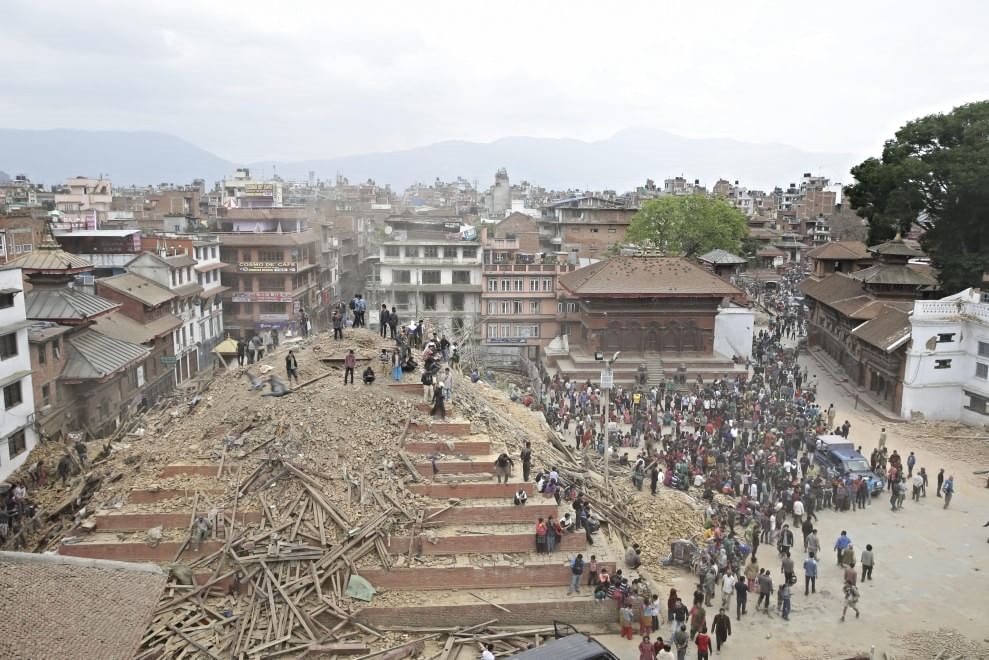

Disaster Law and Displacement in Nepal, Ctd

/Photo: Domenico

Last week I wrote the following about Nepal's building codes contributing to seismic vulnerability:

Nepal ranks near the bottom in a list of countries on preparedness for natural disasters. Despite being located on a known fault-line, Kathmandu, like Port au Prince, did not develop stringent building codes, zoning laws, or urbanization management plans to mitigate risk. What plans do exist have not been enforced.

And weak building code standards and enforcement did contribute to widespread infrastructural and human losses. But engineers are starting to find evidence - from buildings that did not collapse - that construction standards may be improving in Nepal. Simple details like bending steel rods around vertical bands has helped some buildings stay standing, which, while not salvaging the building itself, saved human lives:

These are precisely the construction details that were absent in the wreckage of many of the schools that collapsed on students and teachers in China’s Sichuan Province in 2008.

Miyamoto said Nepal’s two-decade effort to improve building codes is important, but that adoption of new norms and habits by contractors there and in many other developing countries is likely more a function of spreading understanding of why such simple steps make a difference.*

“They have to know why that bend matters,” he said. “A few extra seconds of effort can keep a building from falling on their kids.”

He and others have credited the sustained work of Nepal’s National Society for Earthquake Technology and nonprofit groups such as GeoHazards International in helping spread such insights.

But they are racing the clock in many ways. The same is true around the world.

The need for more stringent building code regulation appears to be getting more attention in nearby India as well, where low, mid, and high-rise buildings share the same minimum building code standards (h/t Andrew Revkin).