If you've been following this blog you've probably noticed that I've been exploring the environmental impacts of marijuana policy for some time now (see archived blog posts on the topic here). While so many states have either legalized or are close to legalizing marijuana, almost none of them have created a regulatory framework to address environmental issues.

Since May I've been working on an article about marijuana and water rights. Water allocation is regulated at the state level, so there are a number of different water rights systems in the United States. My article is the first to look at these various rights regimes and consider how they will interact with the marijuana industry. The full draft of the article is now available here. Below is the introduction:

In late June of 2015, a convoy of vehicles carrying enforcement officers from four different counties of northern California drove up and into the remote and rugged slopes of Island Mountain. The mountain had been given its name by 18th century settlers who observed that it was nearly surrounded by the waters of the Eel River and its tributaries. Today it represents “the dark green heart of the Emerald Triangle,” a region known for its prolific cultivation of marijuana. The enforcement officers conducted open-field searches on private lands, and by the end of the week-long ‘Operation Emerald Tri-County’ had confiscated 86,578 marijuana plants.

While police raids of marijuana farms is nothing new for the area, this particular operation raised some eyebrows. Unusually for a raid of this magnitude, no federal officials were involved – the raid was a wholly state operation. Since legalizing the medicinal use and cultivation of marijuana in 1996, California has been reticent to allocate state resources towards marijuana enforcement, decriminalizing possession of small amounts state-wide in 2010 and capping civil fines at $100. Also unusual were the lands being targeted by the county officers. Seventy percent of marijuana plants seized by law enforcement are illegally grown on public lands, but this operation went after privately held marijuana grows with some measure of legal protection under the state’s Compassionate Use Act. Until this point, a state raid of private lands was uncommon. The raid thus signaled a shift in the enforcement of marijuana laws, but not because the counties were cracking down on marijuana per se. Marijuana, like every other crop in the state, had fallen victim to water scarcity.

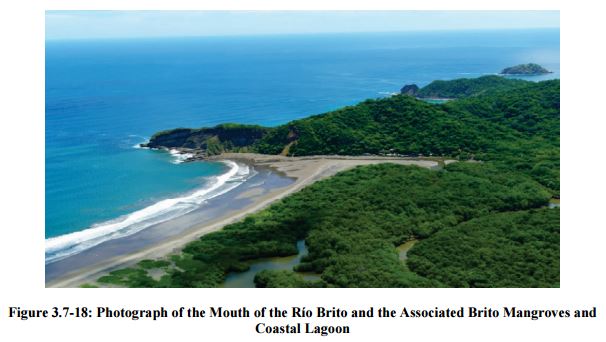

Months earlier, in January of 2014, the Governor of California issued a drought state of emergency in response to ongoing shortfalls in freshwater supplies. The declaration asked state agencies and officials to “take all necessary actions to prepare for these drought conditions.” Since then, the drought in California and across the United States has become a mainstream topic of conversation, dominating headlines and forcing governments to re-examine their water regulations. Water scarcity affects virtually all sectors of economic life, and as an agricultural commodity, marijuana is not immune. There is a paucity of research on marijuana and water supplies, almost certainly due to the covert nature of marijuana production. But in March of 2015, the first credible scientific study of the impacts of cultivation on water resources found that the demand for water to irrigate marijuana plants often outstripped water supplies. Data from the study came from the Eel River watershed.

‘Operation Emerald Tri-County’ is the clearest sign yet that the rapidly evolving forces of marijuana legalization and water scarcity are about to collide. The enforcement officers may not have been joined by federal officials, but they were accompanied by personnel from the state Department of Fish and Wildlife on suspicion of water abuses. Later the four counties claimed the raid itself was motivated by violations of state water regulations, not marijuana cultivation. After finding unpermitted stream bed alterations, diversions, and reservoirs, the officials moved to confiscate the privately grown plants.

In the aftermath of the raid, it became clear that the environmental intentions of the state may not have produced the greenest long-term consequences. Several victims of the raids were members of a political action group working with the counties to draft ordinances that would increase transparency and bring growers into compliance with environmental laws. The group’s director was dismayed that the raid would force growers back into the shadows, away from the state and county’s regulatory framework. A previous effort in 2010 was successful in partnering private growers with county officials to monitor plants and facilitate regulatory compliance, but a federal raid and subpoena of the program’s paperwork shut it down and broke up the partnership. While states can and should enforce water laws in the marijuana industry, doing so without alienating the regulatory targets will be challenging.

This is especially true when considering the pace and mechanism of marijuana legalization initiatives. Marijuana is already legal for recreational use in Colorado, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and Washington DC. Between now and election day 2016, an additional 14 states may place marijuana legalization initiatives on their ballots. In addition, 23 states and Washington DC have legalized medical marijuana, with up to seven states pending legislation. The fact that legalization is largely taking place through ballot initiatives suggests that the public won’t be waiting for state governments to get their regulatory ducks in a row. A majority of Americans favor marijuana legalization, raising the likelihood that state water law doctrines will be tested sooner rather than later.

Reconciling marijuana legalization within the structures of water laws and regulations reveals two broad conclusions. First, for many states the legalization of marijuana is likely to strain existing water regulation resources, disrupt water markets, and interfere with water rights. Marijuana is arguably the largest cash crop in the United States, and while the industry has already been using significant water resources, simply enshrining historical uses is not a viable option for many jurisdictions. On the other hand, states must bring marijuana producers into the fold lest the industry continue to operate in the shadows, and doing so will require some accommodations for producers to use water resources.

Second, and conversely, water scarcity will play an increasingly large role in the development of the marijuana industry. The tri-county raid set a precedent that more law enforcement officers and state agencies are likely to follow in order to safeguard precious water supplies. Even well-established water rights in the agricultural sector have been cut and re-negotiated, and marijuana producers joining the regulatory fray will need to navigate the various idiosyncrasies of centuries-old water laws to maximize their allocations. States are likely to place increased scrutiny on producers who choose to grow or irrigate outside of legal channels.

These broad conclusions stem from a systematic analysis that addresses the gap in understanding the relationship between water rights and marijuana legalization. Section II begins by describing status quo marijuana production taking place outside the context of state water law doctrines. While marijuana can be grown sustainably, unregulated production often leads to illegal and destructive water practices affecting downstream rights holders.

Sections III and IV envision a legal marijuana market governed by the predominant doctrines of US water law: prior appropriation and riparianism. Each system presents a unique set of legal and regulatory challenges, and for states like Colorado, these challenges are already evident. In the American West, prior appropriation states will need to adapt to the relatively rigid nature of priority water rights, as well as the federal government’s outsized role in water allocation and marijuana prohibition. States employing riparianism or regulated riparianism will have a slightly easier time incorporating marijuana cultivation into existing systems, as long as the doctrinal or regulated administration of water rights is holistically applied to the legal marijuana industry.

In Section V the theoretical becomes reality. California’s uniquely mixed system of riparian and appropriative rights provides a number of opportunities for marijuana cultivators to come into compliance with water laws. However, the state’s decentralized and haphazard approach to marijuana regulation creates uncertainty in the marijuana industry. That uncertainty bleeds into the administration of water rights despite the intentions of both cultivators and regulators.

Section VI concludes with recommendations for states in the process of legalization. By applying water laws to the emerging legal marijuana industry, this study identifies a number of key trade-offs states must make in reconciling marijuana cultivation with water scarcity. This section considers the costs and benefits of decentralization, restrictive cultivation licensing, and the “no action alternative.” While water laws will occasionally clash with the new marijuana economy, this Article identifies opportunities to smooth the transition.